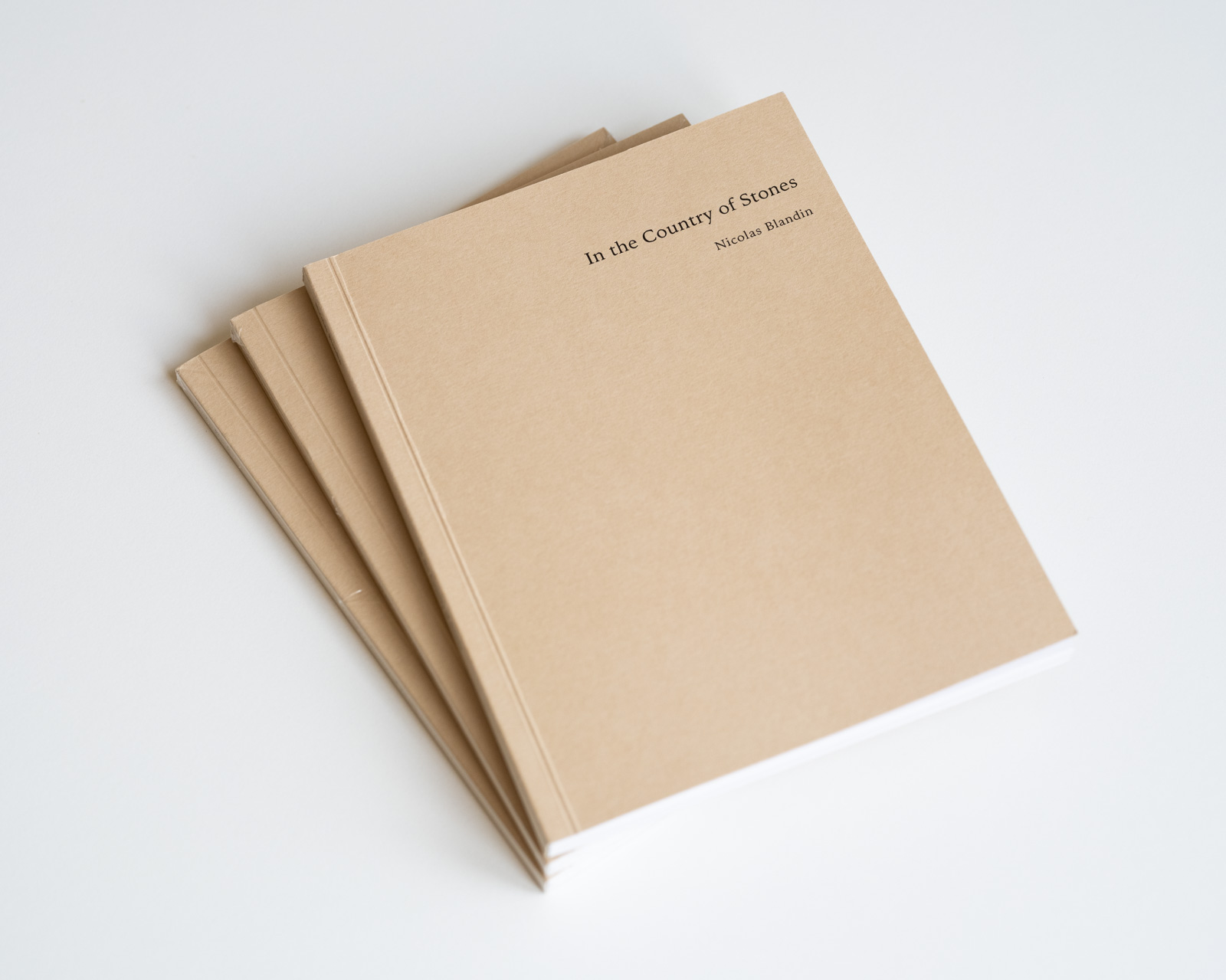

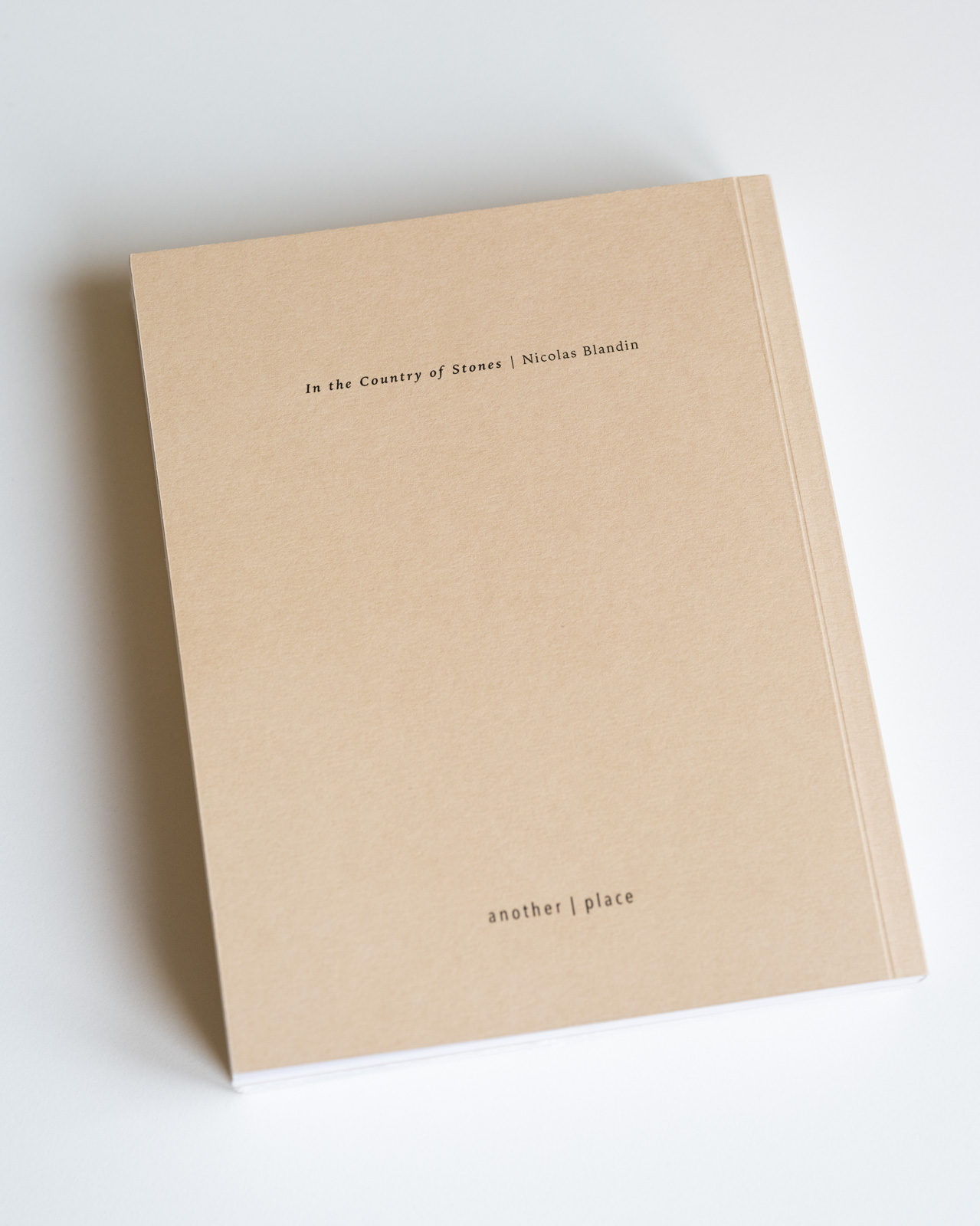

Book ‘In the Country of Stones’

76 pp / 150 x 190mm

Perfect Bound

Fedrigoni & GF Smith papers:

350gsm Colorplan cover

170gsm Uncoated text

Publisher: Another Place Press

ISBN 978-1-9997424-0-9

Edition of 150, sold out.

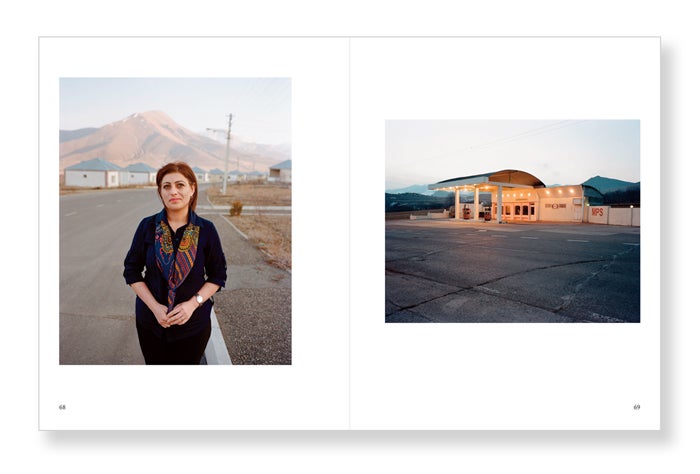

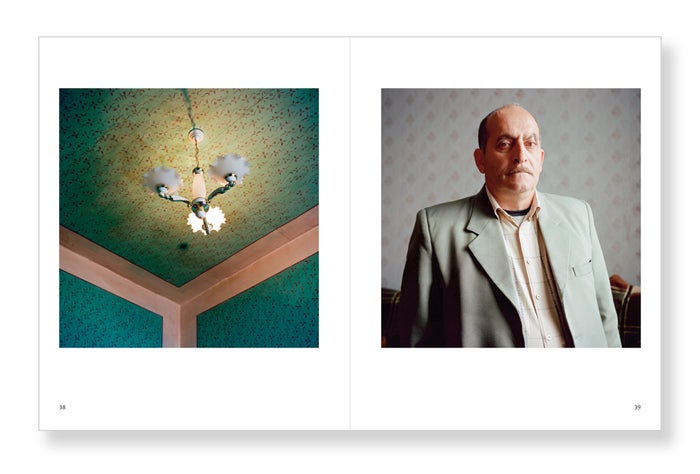

I was seven years old when I first heard anything about Armenia. It was thanks to a seven-inch record played at home – Pour toi Arménie, the charity song written by Charles Aznavour to raise money for Armenians affected by the 1988 Spitak earthquake. Back then I couldn’t have known that over two decades later I would actually go there.

In 2013, my girlfriend and I received a postcard showing Mount Ararat, the snow-capped volcano that is a national symbol in Armenia. That postcard sparked a first hitchhiking trip through Armenia in September the same year. On that trip, my girlfriend and I discovered a fascinating place — a land of contrasts, laden with history. We had heard about the legendary Armenian hospitality, but we were still humbled by the level of openness and generosity we encountered. During those three weeks on the road we had the strange feeling that we had reunited with distant relatives, and we promised ourselves we would return. I therefore seized a volunteering opportunity at Spitak’s YMCA and came back in February and March 2014 to produce pictures for a guidebook presenting historically and culturally relevant sites in the re-emerging city of Spitak, which was destroyed during the 1988 earthquake, shortly before the dissolution of the Soviet Union and Armenian independence.

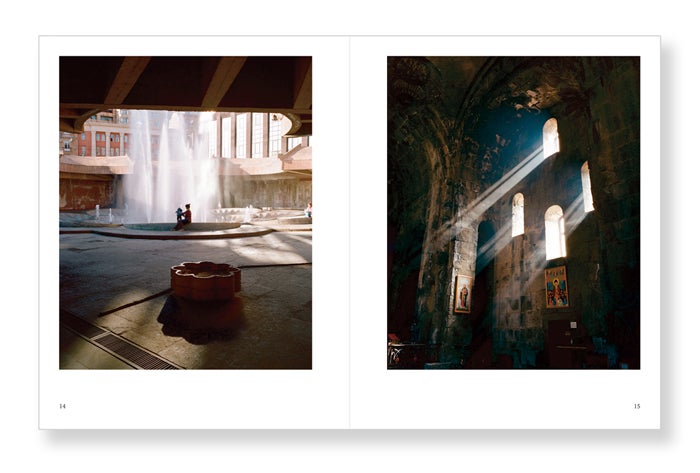

In Armenia, memory and topography are inextricably intertwined. Multiple layers of memory are visible in the landscape. There are, for instance, the imposing remnants of 71 years of Soviet rule, the scars of an earthquake that run deep in the collective memory, and the repositories of the memory of the Armenian genocide, which still lacks formal recognition from various governments around the world. The landscape also reminds us that Armenia was the first state in the world to adopt Christianity as its official religion (as early as 301 AD). Crosses not only appear in cemeteries and monasteries and carved in stone, but also incidentally in the shape of electric poles, shoe embroideries and, more surprisingly, in a Soviet monument (page 12). It is tempting to see the stones recurrent in the landscape as a metaphor for collective memory, for both are shaped and marked by the passing of time and historical events. The present is more elusive in this politically and geographically landlocked, post-Soviet country. But no matter how harsh the economic reality might be, daily life goes on according to its own rules and concept of time, with undeniable moments of grace and warmth.

The images in this book are the result of a personal journey. They are partial, subjective, selective, even oblique. They do not amount to a definitive vision of the country. How could they even presume to record a nation in such a state of flux? In my photographs, I am seeking to tell my own story, as well as the stories of others, as honestly as I can. Rather than documenting the history and the landscape, my approach to both is rather more poetic and lyrical. And yet, to borrow Jocelyn Lee’s words, photographs, unlike paintings or drawings, remain “mysterious but irrefutable anchors to a real event in space and time”.